By Rowland and Sue Hill

The walk to Dodinga village was on a single lane track through dense tropical rain forest. There were occasional glimpses of the narrow creek that gives Dodinga fishermen access to open-water fishing grounds from their village. Traditional boats lay on the stream’s muddy banks, fishing nets dried.

In the village, trees were heavy with nutmeg, and there were cassava, sago and taro plots. Families of small goats, chooks and splendid roosters with rich red combs and golden hackles, ranged freely. It’s a subsistence life in Dodinga, with sales of some fish and nutmeg in nearby Ternate and Tidore Islands generating a little cash.

Dodinga, on the island of Halmahera in northeastern Indonesia, is typically rudimentary in this remote area, with 80 or so neat but simple homes. A local store sells a few basic needs. There is a primary school and a couple of mosques.

We guessed the village’s population at around 500 or so, its people seemingly healthy and happy, with calls of ‘salamat sore’ and ‘hello mister’ as we arrived. The tribes of clamouring kids loved the swim goggles and crayons we passed around.

Dodinga in History

Up the track from Dodinga are the remnants of a Dutch fort, one of 44 built in the Banda and Maluku Islands during the brutal Spice Wars of the 16th and 17th centuries as the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and English fought to control the international trade in nutmeg, mace and cloves. Otherwise the village is little known and generally unremarkable.

Yet Dodinga has an important place in history. It was here, almost 170 years ago, that a self-educated naturalist, in bed and sweating and shivering through a malarial fever, jotted down his conclusions on the evolution of species. These notes were heretical, challenging understanding of the natural world, and religious doctrine of the time.

Alfred Russel Wallace in Dodinga

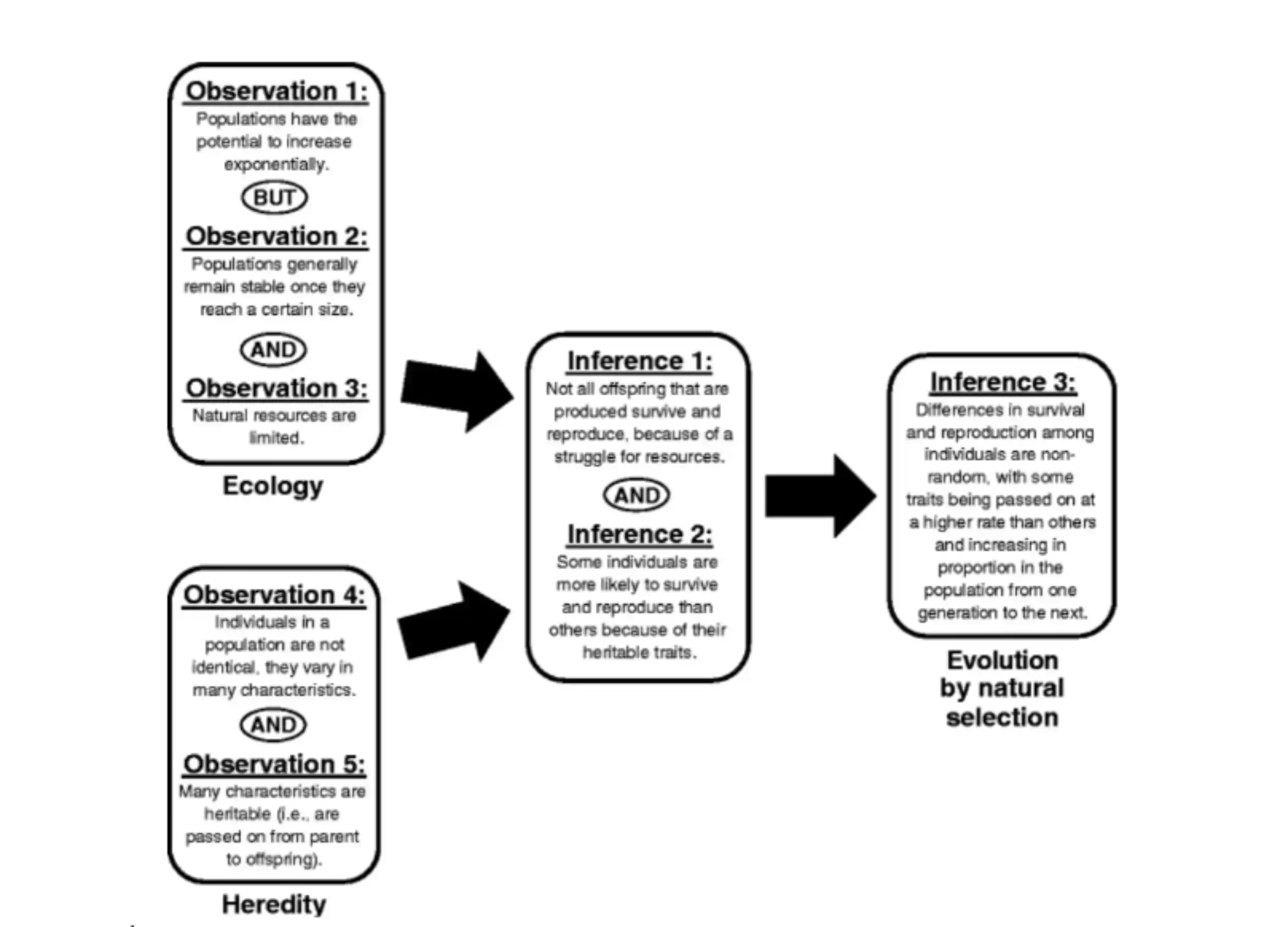

The naturalist was Alfred Russel Wallace. His notes were his conclusions on the process of how living organisms changed over time in response to the environment in which they lived.

The year was 1857. By then Wallace, 34, was deeply experienced, collecting and describing thousands of insects, bugs and birds, many previously unknown to science. He was an astute observer, a determined collector and gifted taxonomist – perhaps borderline Aspergic. He self-funded his research and fieldwork by selling specimens to wealthy English collectors clambering ‘to own new discoveries’.

From a working-class background Wallace was without formal education. Realising his thesis would be controversial, Wallace sought reassurance from the already respected naturalist Charles Darwin – 24 years his senior and whom he had previously met – posting his Dodinga notes to Darwin under a covering letter written in Ternate after his recovery.

The Birth of the Theory of Evolution in Dodinga

Darwin, still untangling his understanding of the mechanism of evolution with insufficient confidence to publish, was stunned. On the other hand, Wallace after three years intense on-the-ground collecting in what is now eastern Indonesia and earlier in the Amazon, had already written about his observations in his little noticed Sarawak Law paper published in 1855.

Professor Giacomo Bernadi, of the University of California, holds the Sarawak Law essay to be as crucial to Wallace’s thinking on evolution as was Darwin’s visit to the Galápagos Islands when he circumnavigated on The Beagle in the 1830s.The British Museum’s Dr George Beccaloni describes Wallace’s letter to Darwin (The Ternate Essay) as ‘probably the most important scientific paper in the history of biology’.

Fearing his life-long work on natural selection could be scooped, and urged by friends in the scientific community, Darwin rushed On the Origin of Species into print, confirming his name in history. Yet despite the ground-breaking work he’d already published outside the world of science Wallace is largely forgotten.

While one chapter of On the Origin reflects Wallace’s thesis, critical reviewers of the publication say the chapter was written in the style and words of Wallace’s Dodinga notes and his Ternate essay without any specific source citation. Darwin himself has said Wallace’s ideas were central to his work.

Other reviewers of the events of 1857 have concluded that ‘Darwin and his influential friends in the scientific community conspired to rob Wallace of credit for natural selection’ and described the putative plagiarising of Wallace’s views as ‘one of the greatest wrongs in the history of science’.

On the other hand, others claim Darwin proposed the thesis be called the Darwin-Wallace theory, but the self-effacing Wallace insisted on Darwinism. He published a book of this title based on lectures he delivered in the USA in the 1860s.

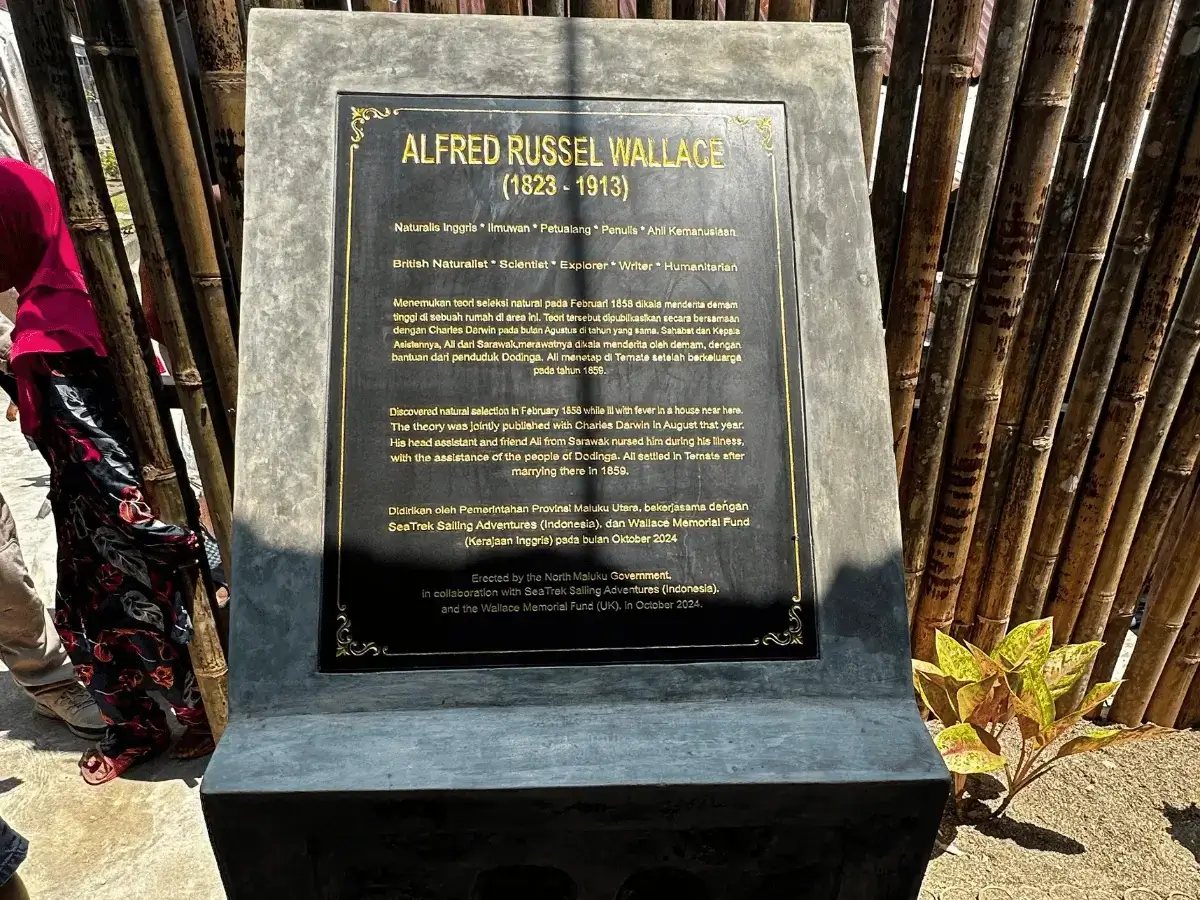

The modest Dodinga house where Wallace survived the malaria attack and penned his notes on evolution is long gone, but its site is the last in a row of about eight modest shacks down a side street opposite one of the village’s mosques. Three days after our visit, the village of Dodinga hosted a visit by the Governor of Maluku, the British Ambassador to Indonesia, Alfred Wallace’s Great Grandson William Wallace, and Dr Beccaloni. A plaque at the side street’s intersection with the track we walked from the wharf to the village was unveiled, recording the importance of the Dodinga events.

Alfred Russel Wallace and the Malay Archipelago

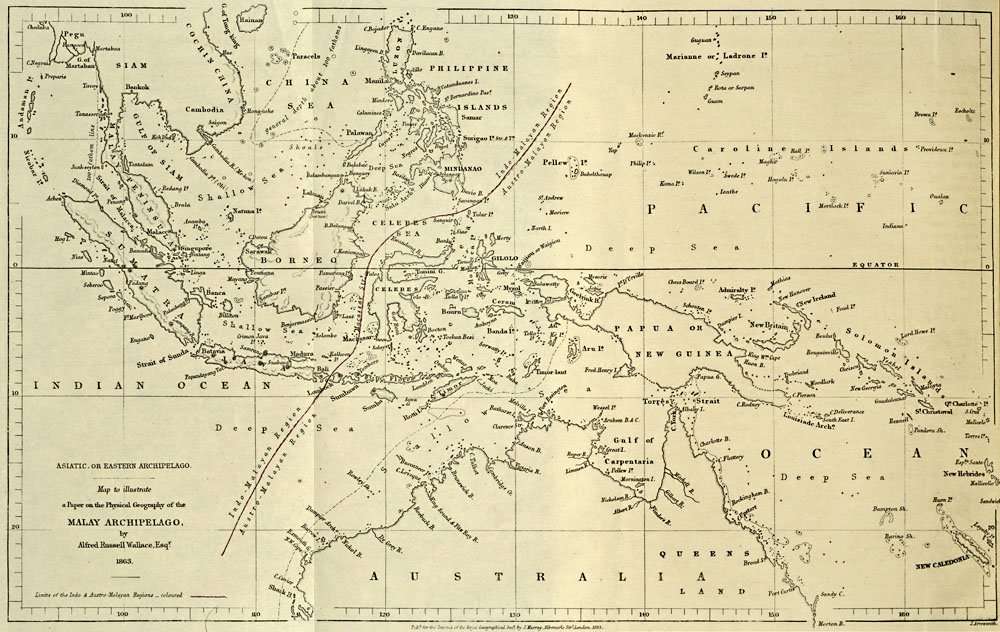

Wallace is familiar to many in the science community through the 22 books he wrote – including The Malay Archipelago first published in 1869 and never out of print – and around 1000 articles and papers. About 250 faunal species are named after him.

There is the Wallace Line, the boundary Wallace identified separating Asian and Australian fauna regions. The line extends from the Indian Ocean, north through the Lombok Strait between Bali and Lombok, then through the Makassar Strait between Borneo and Sulawesi. This underwater trench, formed when Gondwanaland broke up, is 8000 metres deep in places separating many fish, bird and mammal groups – eg carnivores are found west of the Wallace Line, and marsupials to the east.

In Search of Wallace Discoveries in Dodinga

While George Beccaloni rejects suggestions that Darwin was a plagiarist, with a team of supporters, many of them volunteers, he is working to elevate Alfred Russel Wallace’s memory.

There is the Dodinga plaque, and the prospect of reconstruction of the house in Ternate where Wallace lived, just behind the impressive Fort Oranjie. There is a bronze statue of Wallace in the British Museum, and the Wallace Discovery Centre in Singapore. Sir David Attenborough is the Patron of the Wallace Correspondence Project, and comedian Bill Bailey is patron of the Wallace Memorial fund. There is Tim Severin’s book The Spice islands Voyage: In search of Wallace.

We travelled to Dodinga on the Ombak Putih, owned by the Indonesian adventure travel company SeaTrek Sailing Adventures, on the last days of a Spice Islands tour. We knew of the Wallace Line, but this exposure to the details of Wallace’s epiphany in Dodinga, and Darwin’s response to it, was an intriguing bonus. SeaTrek is a keen supporter of the project to elevate Wallace’s profile.

There is a comprehensive website with information that will help others decide for themselves whether Darwin was a plagiarist, or if evolutionary theory should be termed ‘Wallaceism’.